'Recess is where real life happens': Where will children learn everyday skills without canteen stalls?

I love hearing my seven-year-old daughter regale me with her daily recess tales.

Not tales from the classroom — the canteen. Recess is where life happens.

It's where she learns to hold her place in a queue, to speak up when a stall aunty can't hear her, and to count her coins quickly without holding up 10 hungry children behind her.

It's also where she learns that adults, like children, have good days and tired days, and that kindness, even in a busy canteen, rarely goes unnoticed.

"Do you know what time the stall aunty starts work?" she asked me once, referring to her favourite char siew noodle stall. "5.30am!" she exclaimed, eyes wide.

Another day, she came home delighted because an aunty had slipped her a free apple after she bought her meal.

These tiny human exchanges in school were so ubiquitous that we never thought twice about them. Now, they are quietly slipping away.

The dying trade behind our children's everyday lessons

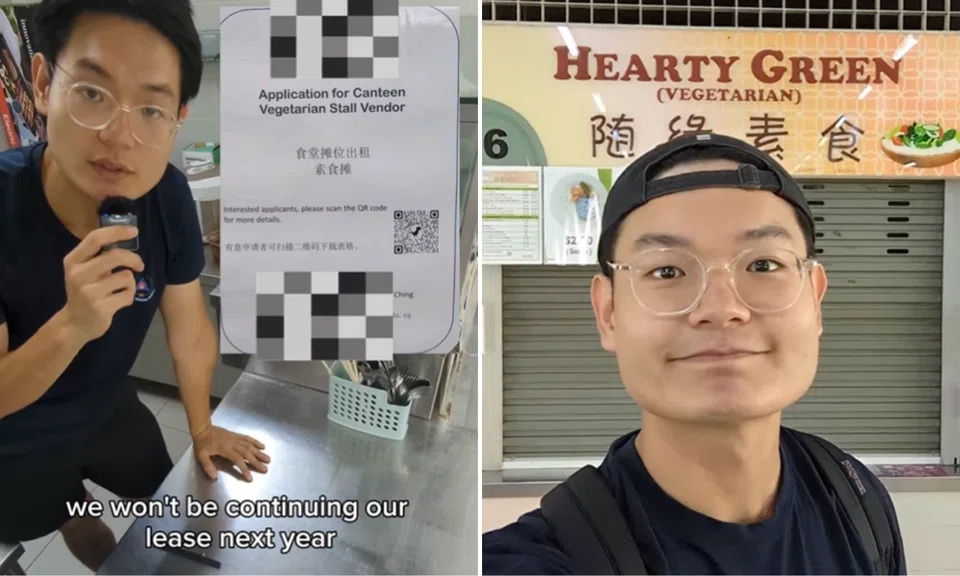

By now, everyone will have heard of the primary school canteen stall owner — 27-year-old Rayner Tan, known online as @veg.eng — who captured Singaporeans' attention with simple videos of his daily interactions with students.

One clip went viral after he gently corrected a boy who tossed a $2 note onto the counter.

Instead of reprimanding him, Mr Tan simply placed the note back in the boy's hand and said: "Pass me properly." The exchange ended with them thanking each other. It was a moment of real-world learning no worksheet can replicate.

But despite the overwhelming support, Mr Tan announced that he is shutting his stall.

A complaint about the viral clip was the tipping point, on top of the pressures that already make running a school canteen stall nearly impossible: long hours, rising costs, unpredictable footfall and razor-thin margins.

Many Instagram users expressed dismay. One wrote: "So much kindness, and gentleness in the way you teach the right values."

Another lamented: "Our canteen aunty back then before the existence of video recordings does [sic] the same too. They taught us to say please and thank you. Taught us manners and fed us with the best memorable food."

Mr Tan's story is not an anomaly.

Schools across Singapore are struggling to fill canteen stalls. A check on the Education Ministry's website shows at least 50 ads calling for canteen operators.

With no applicants in sight, many are turning to central kitchens and automated dispensers. By January 2026, 13 schools will rely entirely on catered meals instead of individual hawkers.

There's no doubt the kids will be well-fed. MOE said central kitchen operators need to provide at least one full meal priced at no more than $2.70 in primary schools and $3.60 in secondary schools.

They must also follow the Health Promotion Board's Healthy Meals in Schools Programme guidelines and provide a good variety of food choices.

Still, I can't help but feel the loss.

The warm, messy, noisy microcosm of the school canteen is slowly being engineered out of existence.

What our children stand to lose

A canteen is not just a place where children eat. It's where they practise being part of a community.

Much like the playground — where kids learn to navigate social dynamics, handle unkind comments, and settle minor conflicts — the canteen teaches its own set of everyday skills.

Beyond how to manage money, it's also where they decide whether to spend their last $2 now or save it for tomorrow's treat.

It's there they learn to look adults in the eye, speak respectfully, and take gentle correction in their stride.

These interactions form the earliest foundation of how a child moves through public spaces with confidence and empathy.

I'm not blind to the concerns. Parents want healthier food, and some stalls charge more than they should for frozen or processed meals.

Central kitchens offer consistency and safety. They are also fast. Automated dispensers can deliver food in minutes, keeping queues moving even during peak recess.

But replacing humans entirely reduces recess to a transaction, not an experience.

If food becomes just another item to collect from a machine, what space will children have to learn the soft skills that matter?

Canteens build character, quietly, and without fanfare

When I asked my daughter how she'd feel if her canteen were replaced by vending machines, she didn't hesitate.

"I don't really like vending machine food," she said matter-of-factly. "And I'll miss talking to the aunties who ask me, 'What do you want to eat?'"

It made me realise that these are the moments she holds on to. These small interactions stay with children long after they forget their spelling lists.

My favourite canteen memory is of an uncle who sold Indomie noodles only on Saturdays — a treat I looked forward to after CCA. I remember exactly how he made it, and I still try to recreate it today.

How to keep the canteen from becoming just a memory

If we want to keep this part of childhood alive, we can't just mourn what's fading. We need to rethink what comes next.

Could schools consider hybrid models rather than full automation? Central kitchens may be necessary, but they don't have to replace the human element entirely.

Some schools, like Yusof Ishak Secondary, already combine catered meals with a few manned stalls. Even one or two stallholders can give students the human touch that machines cannot.

Canteen operators also need stronger, more practical support.

Low rent alone isn't enough when stallholders are juggling so many challenges at once.

Schools could explore subsidies during exam periods and school holidays, or provide a shared manpower pool during peak recess hours.

Another option is to let canteen vendors cater for school events or even the wider community. And instead of fixed rents, schools could consider revenue-sharing models.

These small shifts could make the difference between a stall surviving or shuttering.

We need to recognise the value of canteen aunties and uncles as part of a school's ecosystem, not an afterthought.

If we see them as informal educators who teach manners, patience, and social skills, then keeping them becomes a priority, not a nice-to-have.

My son is four now. In slightly more than two years, he'll enter Primary 1. And I genuinely don't know if there will still be a canteen aunty or uncle waiting to greet him.

I hope so. I hope he'll meet a person behind the counter — not just a machine waiting to dispense a meal, but someone who will help shape who he becomes.