TikTok is paying S'pore Gen X 'aunties' to use app

Teo Kai Xiang for The Straits Times

At Tiong Bahru Market, Ms Christina Gwee, 50, armed with a tripod and two smartphones, is setting up her TikTok show in front of a fruit stall.

Once the live stream begins, her on-screen persona "Aunty Jin" emerges, speaking at breakneck pace into a $30 detachable microphone as she greets her first viewers by name, much like a shopkeeper would her regulars.

Only here, the mother of two boys, aged 17 and 19, adds: "Please help me like and share the channel."

Once enough viewers have piled in, she begins her spiel, hawking $5 Turkish plum boxes and $2 heirloom tomato punnets to an audience that soon grows to 100 online.

Theirs is a rapid-fire exchange as she holds up fruit after fruit, asking the stall's owner to explain an item while she responds to messages.

One viewer asks: "Is it sweet?"

"Boss, I want tomatoes, can deliver?" goes another.

"Skibidi," writes one user.

In a testament to how commonplace content creators have become in Singapore, people mill about doing their shopping, paying her no mind while she addresses her smartphone camera.

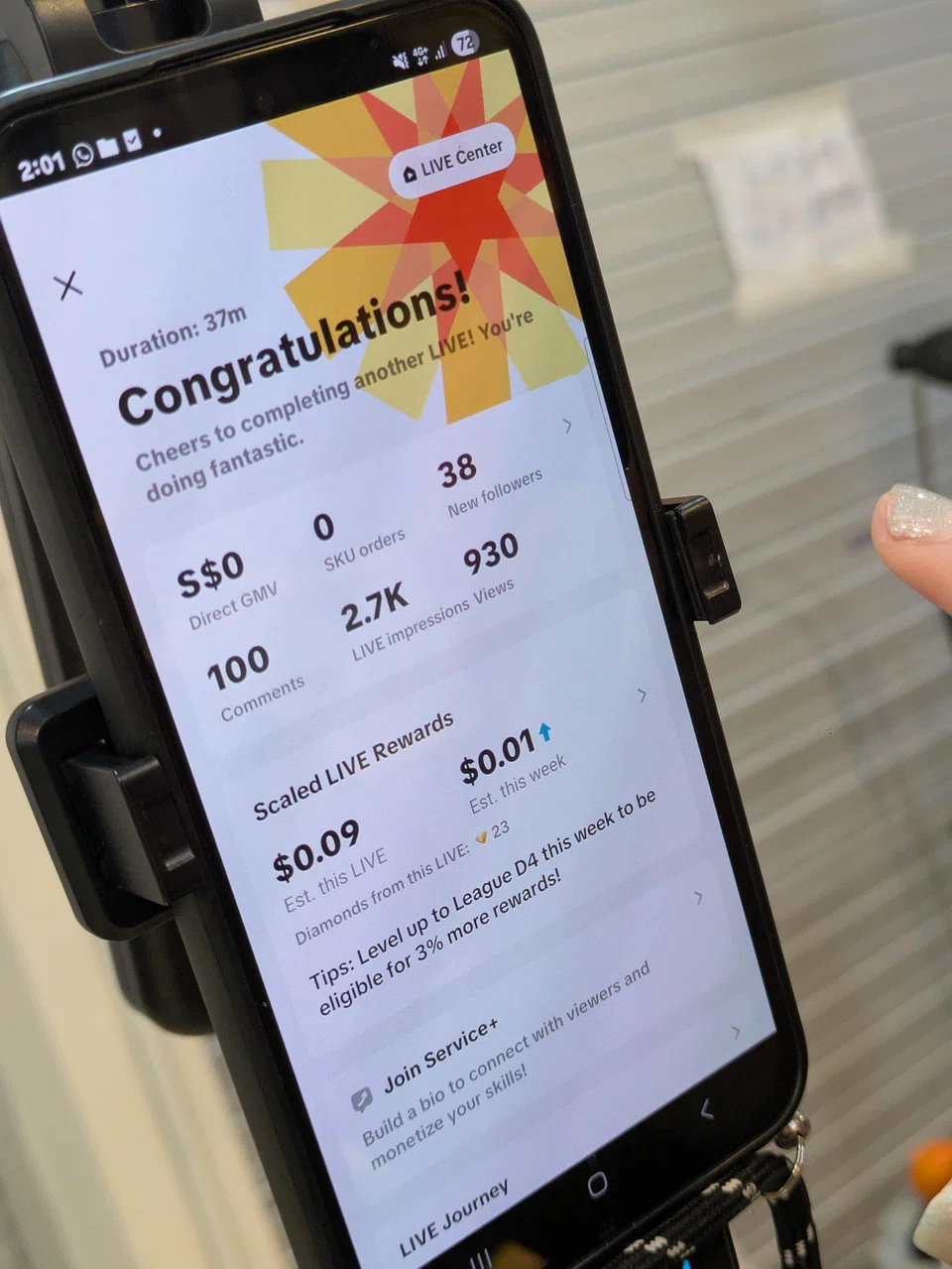

By the end of the 30-minute live stream, she has gained over 2,700 impressions - the cumulative number of people who have seen it - as well as 38 new followers for the fruit stall's social media account.

Though no sales materialised - the business' TikTok shop is not yet operational - Aunty Jin considers this a victory. An inaugural live stream for the fruit stall, it is just a taste of the sweet fruit of sales to come, she hopes.

Inside the school of TikTok

Ms Gwee, a former cafe owner, is one of more than 200 recent graduates of TikTok's Live Host Academy, part of the social media platform's aggressive expansion of its e-commerce operation.

In July, TikTok told The Straits Times the company aims to train 400 live-selling hosts in Singapore in 2025 - though not all of them are Gen Xers aged 45 to 60.

According to a TikTok spokesperson, the programme draws a diverse mix of applicants from all walks of life, with varying levels of experience with content creation.

The month-long introductory programme includes four hours of lessons, online and at TikTok's One Raffles Quay office, as well as meetings with TikTok's army of e-commerce account managers who match content creators with brands. Content creators are also briefed on dos and don'ts. For instance, gambling content is against TikTok's guidelines.

Ms Gwee, part of the academy's first cohort of students in April, says it taught her the essentials of the app's interface, how to deploy both lighting and timed discounts effectively, and how to create promotional banners using the free image-editing tool Canva.

However, beyond these techniques, the real hook lies in the $1,500 cash incentive for academy students like her who manage to complete 15 two-hour live streams.

"If you focus on conversions, usually you will be very demoralised," says Ms Gwee.

In this context, conversions refer to sales made during a live stream. Live sellers earn a commission on these sales, which varies from 1 to 25 per cent, depending on the product.

"In the first streams, you may get only $10 or $20 a stream because your followers and skills are not there."

Another incentive is the platform's video partner programme, which sends free samples to creators, with the expectation of them shooting 30 affiliate marketing videos a month. Those who complete this task can earn $300.

While content creators have long been paid for sponsored content, what makes this arrangement unusual is that the payment comes directly from the platform's owner - regardless whether a single sale is made.

Beyond training, there is also job placement. TikTok's account managers play an active role in matching academy students with brands on the lookout for live-stream hosts, another useful tool for those new to the business.

In WhatsApp group chats, they blast the academy's newly minted, aspiring live streamers with lists of businesses selling on TikTok. When live streamers express their interest, account managers reach out to these businesses on their behalf.

"On my own, I don't think I would be able to reach out to them," says Ms Gwee.

Collectively, these perks create incentive and space for newcomers to develop their skills, with less pressure to turn in a profit immediately.

After closing her cafe in 2019, which she ran for seven years with her husband, Ms Gwee, a polytechnic diploma holder, worked part-time in event sales while raising her kids.

Since she started live-streaming in 2025, she has conducted more than 200 streams, mostly for brands selling food and kitchen goods.

Now that her income from TikTok has picked up - she estimates earning between $2,000 and $5,000 each month - she has decided to trade in old-school sales for its new-fangled online update.

Creating new converts

"I did not have a very good impression of the app at first," says Ms Gwee. "I thought it was just funny dances and funny things. I always told my sons, 'There's no substance.'"

"Now, 80 per cent of my time on social media is on TikTok," she adds. "Most of it is spent watching the top streamers - how they stream, how they talk, what products they carry, what makes them so successful."

In her media-savvy family, she is TikTok's newest convert. Her father, a retired kopitiam operator aged 77, was an early adopter of the app, while her sons are content creators.

Her younger son, an Institute of Technical Education student, has produced TikTok videos for businesses as a side hustle. Meanwhile, the older boy, a polytechnic student studying media arts, uploads his music on the platform.

While her new-found TikTok embrace has led to many cries of "Mum, stop being embarrassing", it has also created bonding moments when the kids chime in with suggestions on how to improve her lighting or sales pitch.

She thinks her appeal is her relatability, especially to the older generation.

"I have fans and audiences who are old folks," she says. "They have difficulties learning TikTok and purchasing things on the app. You have to teach them."

One of them is a 70-year-old woman she met while volunteering at National Cancer Centre Singapore, who did not know how to complete a transaction on the app.

"She fractured her leg and couldn't go out of her house to buy anything," Ms Gwee recalls. "I helped her set up her account. Every time I live-stream, I'll send my link to her. The stuff I'm selling is really meant for her."

Emotional roller coaster

In a ninth-storey unit of an industrial complex in Ubi, Ms Margaret Tang sits in a backroom, hidden behind aisles of packages, kitchen appliances and TikTok-famous water bottles.

From this makeshift studio, the 56-year-old homemaker and mother of a teenager is live-streaming to an audience of 10.

There is an improvised and chaotic energy to her show. She frequently stands up while speaking, cropping her face out or obscuring it with a promotional banner, as she reels off the 10 functions of the Instant Pot, a combination pressure cooker.

Reading out examples of the dishes one can make from an Instant Pot recipe book, she is momentarily tripped up.

"Actually, I'm not sure if there are people in Singapore who like making a good Texas-style chilli," she admits after a pause, midstream.

Then she pivots and recovers her conversational footing. "Red bean soup, pulut hitam - all of it can be done in 20 to 30 minutes instead of hours."

Localising the American product for Singaporean viewers, she says: "Now, what I like to do is ramen noodle soup…"

At the end of her spiel, she asks if there are any questions. None is forthcoming. Dead air follows. She takes that as a cue to move on to the next product. Rinse and repeat.

At the end of her two-hour stream, Ms Tang makes just one sale: a $253 Instant Pot.

"It can be an emotional roller coaster," she tells ST after her live stream, which she sees as another step on her journey up the content creator ladder.

"If there's no response, no traffic, no purchases, it can leave you with a very deflated feeling."

Despite the day's low sales, Mr Jarrett Yeo, business development manager of importer Focus Global, who hired her for the stream, is certain that TikTok is the future of commerce.

"Margaret began her journey not long ago," Mr Yeo, 43, says. "Creators like her sometimes do not find good chances to work with merchants, because merchants might think they are nobody. For us, we give everyone a chance. Hopefully, when she gets big and has more followers, she doesn't forget us."

These days, TikTok's top live sellers are in hot demand, and must be booked as long as two months in advance. They can command regular audiences of 200 concurrent viewers, earning up to $2,000 in a two-hour stream. Top sellers tell ST they make as much as $20,000 a month.

"Not even in a mall will you see 200 people in one minute," observes Mr Yeo.

Among the selection of goods he imports is the TikTok-famous BruMate water bottle, costing $69.90, said to have a 100-per-cent leak-proof lid and the ability to keep beverages cold for over 24 hours.

"When the BruMate is on the shelf, you don't even look at it. But when a creator vouches for this brand, it's a different result compared with listing it on Shopee or Amazon," he says.

He adds that during the 7.7 sale in July, he racked up over $100,000 in live-stream sales over one week.

In his view, consumers are shifting away from bricks-and-mortar stores to swiping and paying from the comfort of their home. It also helps that meeting them through online channels cuts down on labour costs and consignment issues that stem from selling in-person.

Catching the TikTok virus

Ms Tang has long fantasised of being a content creator on YouTube - one who makes videos about jewellery crafting or teaching the English language.

The problem is the long-form video platform has long ago outgrown its rebellious and grungy early internet phase, when creators could get clicks with low-resolution and minimally edited footage.

Now, the channels that dominate YouTube are professional endeavours with video-editing suites, expensive camera equipment and, sometimes, a cast and crew numbering in the dozens.

In contrast, TikTok does away with all that in favour of whatever content is enthralling enough to hook someone within the first three seconds.

"Some of the affiliate marketing videos are so raw - bad lighting, no script, just talking to a camera like an ordinary person," notes Ms Tang.

"It just makes it a lot easier to be yourself. You don't have to be an actor. You don't have to be a TV personality. If you want to speak Singlish or Hokkien, that's okay."

For Ms Tang, who has a university degree in computer science, live streaming is just her latest gig. She has been a systems engineer at Hewlett Packard, a short story writer, a voice-over artiste and, briefly, an intern at the Ministry of Health's marketing department.

It was a life free from short-form videos until 2021, when she caught the TikTok bug on quarantine, after testing positive for Covid-19.

She spent days and nights glued to the small screen, but uninstalled the app at the end of her lockdown.

"It takes so much willpower to say, I'm going to do just 30 minutes. There's no such thing," she says. "You see one clip and it goes on. Next thing you know, two hours are gone. I had to go cold turkey."

Her reintroduction to the app through the platform's training programme was what made things stick.

"When I started, I didn't know what I was going to sell or do," she says. "I didn't really have a strategy. It was the TikTok Live Host Academy that did the matching.

"They looked at my profile and figured out what I can sell. They decided, 'Okay, given her profile, being a homemaker, she's probably going to do better with household and kitchen stuff.'"

After a miserable first three live streams selling bedsheets and blankets that notched negligible sales, Ms Tang made the pivot to kitchen goods and appliances.

As an "obsessive learner" who has spent years flipping through recipes and watching kitchen how-tos, she says she now has something to say about practically anything kitchen-related.

Tick tock, TikTok's Gen X appeal

Ms Tang's coursemates at TikTok's academy now use a group chat to share advice and inform others when they are going live.

They have wised up to how live streams that experience an influx of interest are more likely to be recommended by TikTok's algorithm to other users. As such, they use this knowledge to give one another an edge.

"Sometimes, we hop in and say 'Hi', give our likes, support the stream, to try to get the algorithm to support them a little," she says.

Members of the group also flag "scammers" to one another, such as malicious accounts which record segments of their live streams and repurpose them as new affiliate marketing videos, passed off as their own content. These are all part and parcel of life on a platform where videos are endlessly remixed, says Ms Tang with a shrug.

She remains hopeful about her prospects with the app.

Her most successful live stream was a roadshow for home appliance company Mayer, which saw over 100 concurrent viewers on the stream, firing away with more questions than she could answer, while they snapped up discounted goods.

"TikTok gives you a way to sort of run a business, but you don't have all the hassles," she says. "You don't have to invest in the product. You don't have to deal with the logistics. You just go there and sell."

With three months to go to her 57th birthday, Ms Tang believes she is on a ticking clock.

"I've 15 to 20 good years left, so I don't want to be working nine to five," she says. "This gives me flexibility. I don't have to show up for work every day. If I don't want to live-stream, I don't schedule a live stream. If I want to start making money, I start calling the sellers."

"In the past, I couldn't sell at all," adds Ms Tang, recalling her unsuccessful stints peddling encyclopaedia and insurance products in her younger years.

"But I'm at a stage of my life where I thought I'd just try something," she says. "If it works, it works. If it doesn't work, I gave it a go. It's a new adventure."

See something interesting? Contribute your story to us.

Explore more on these topics